On a warm July evening of the year 1588, in the royal palace of Greenwich, London, a woman lay dying, an assassin's bullets lodged in abdomen and chest. Her face was lined, her teeth blackened, and death lent her no dignity; but her last breath started echoes that ran out to shake a hemisphere. For the Faery Queen, Elizabeth the First, paramount ruler of England, was no more...

The rage of the English knew no bounds. A word, a whisper was enough; a half-wit youth, torn by the mob, calling on the blessing of the Pope...The English Catholics, bled white by fines, still mourning the Queen of the Scots, still remembering the gory Rising of the North, were faced with fresh pogroms. Unwillingly, in self-defence, they took up arms against their countrymen as the flame lit by the Walsingham massacres ran across the land, mingling with the light of warning beacons the sullen glare of the auto-da-fé. (p. vii)

As a historian, particularly one who concentrated on cultural and religious history, I am very wary of any work of alt-history that introduces radical changes from a simple "what if?" scenario. It is not because I think such speculations are fruitless. After all, not much would be accomplished in historical studies if such questions were not asked daily of almost everything. Rather, it is the sense that for many, perhaps for the authors as much as the readers of such alt-histories, there is a distortion that occurs whenever a focus is shifted to a singular person or event. Unfortunately for me, Larry as Reader, whenever I have to confront these questions of possible historical distortion in a story, Larry as Historian intrudes upon the Reader/Text/Author interpretation triangle, muddying the waters of story analysis.

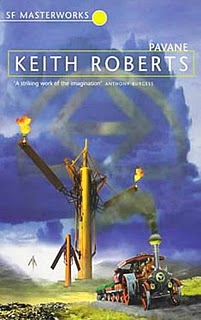

This certainly was the case with my recent reading of Keith Roberts' 1968 novel, Pavane. Roberts certainly crafted a stirring beginning, as indicated by the first two paragraphs of his two-page prologue that introduces the vastly-altered 20th century setting. The year 1588 certainly was a momentous occasion, as some date from it England's rise to international prominence, a position it maintained until the end of World War II. There certainly were precarious conditions within the country, as Roberts does note, as well as conflicts with Spain and to a lesser extent, France. But there are a host of other issues, ranging from social divisions that ran deeper than the newly-formed religious factions to the already well-developed sense of English nationalism, that make it difficult for this reader at least to accept that there was a blithe acceptance of the posited Armada conquest and the full and total restoration of the Catholic Church in England.

Sometimes reviewing a work means that the reviewer has to review his or her own biases and attempt to quell them, if they cannot be suspended for the duration of this piece. For the most part, once I accepted that there was going to be a dissonance between my understanding of history and what Roberts uses as a catalyst for his story, I was resigned to the fact that I would be battling myself in an attempt to enjoy this story and to appreciate what Roberts does accomplish with his six interconnected stories and a brief coda. Despite my misgivings about the rationale behind such an alt-history and despite my puzzlement over some of the implications of the imagined alt-choices that Roberts highlights, there are things of value within this story.

Most of the action of these stories takes place in the early to mid-20th century. The Catholic restoration has been in place for nearly four hundred years, not just in England, but also in the formerly Protestant German states. Technological advancements have mostly been halted, although there are some curious analogues to the Industrial Revolution. The guild system is still largely intact and the populace has been redivided into ethno-linguistic lines (a restored Norman French, Middle English (!), Modern English, Welsh, Scots, Scottish Gaelic, and Latin are now the languages of Court and People). There is steam transport, but the use and power of it is heavily regulated. Learning is concentrated in the hands of the few, and the Papacy has as much influence as in the days of Innocent III. It is an alien world to us, one that frankly seems unrealistic considering the developments in Catholic countries during the 15th-18th centuries (not to mention that of the Protestant-controlled regions during the same time), but the key to these stories is not to focus so much on the backdrop, but instead on the characters' interactions with this alt-environment.

Roberts' characters shine in the stories contained within this narrative collection. With very few characters appearing in more than one story, each of the characters that do appear in these stories typically find themselves confronting the world around them, questioning the order of things and in some cases, wondering about these apparently mystical "old ones" that appear on occasion, hinting at a different reality. Roberts doesn't rush the telling of these stories; he allows the characters to "breathe" and to express their hopes and fears in such a fashion that the reader becomes more drawn to unraveling those little connections between the stories. The prose is very well-constructed, as few words are wasted and everything builds up to a strong conclusion in the Coda. If the reader can accept the plausibility of the narrative overarching the individual tales presented within it, Pavane can feel just like the slow, intricately-constructed dance after which the book is named.

But that is the key issue here. Can the reader suspend his or her disbelief enough to enjoy the rich tapestry of stories? For myself, I struggled throughout. I did appreciate how well Roberts constructed his stories; I just could not accept the premise. Even with the revelations at the end that overturned some of the conceits found within the linked stories, I found myself thinking far too often "this just is not plausible enough!" for me to gain full enjoyment out of it. However, this is a highly individualized reaction and I could see for those readers who want well-constructed stories with interesting characters and prose that makes their concerns feel vivid and "alive" where Pavane would be just the sort of story for them. Recognizing that a work may be a "masterwork" does not mean that one has to "like" it, of course. For me, Pavane was a book whose merits were partially obscured by my own biases and skepticism about the premise behind the stories contained within it. Those biases and skepticism were never fully overcome, thus lessening my enjoyment, if not my appreciation, for this work.

I understand your concern, even though I'm not especially well versed in history - I had similar qualms about Silverberg's Roma Aeterna, which is otherwise a fine book, if a bit too world-weary, by a master.

ReplyDeleteI'm wondering if you tend to be more forgiving if the tone is a bit lighter, I'm thinking about John Brunner's Times Without Number which I found to be very enjoyable, for instance.

As for me it was rather the rather weak tying of the stories together in the end that I found disappointing, the shared universe and filiation seemed a good enough excuse to publish this as a single book.